In 1990 Bainbridge Islanders voted to incorporate the entire island as a city. We believed that local control would protect us from what we had experienced in the preceding decade of unwanted growth.

A primary concern was how the island’s resources—its forests, farmland and water—were being cleared, paved, developed and used up at an accelerated pace. What we wanted was “sustainability,” and that became the centerpiece of BI’s first Comprehensive Plan.

It wasn’t long, though, before our new city government had climbed into bed with the developers it was supposed to protect us from. And when a big corporation came to town proposing a new shopping center in 2013, city staff effectively became part of the development team. The Island’s BI’s Comp Plan, and “sustainability,” appeared to mean nothing. Something had to give.

Controversy over the new shopping center had energized all sides in the debate over growth and development just in time for the 2016 Comp Plan update and public participation meetings starting in 2014. Sustainability advocates focused on climate change, tree protections and the need for a Groundwater Management Plan. Developers and city staff took aim at what they saw as too much “sustainability” in the Comp Plan. They suggested substituting the word “durability” for “sustainability.”

Comparing BI’s natural resources to a pair of shoes or set of tires was audacious and hilarious, but in a sense already a reality. You needed to look no further than the eagerness of city staff to cherry-pick policies from the Comp Plan to support development projects and in the process purposely misrepresent the plan’s overall theme of sustainability.

Sustainability is an idea as old as the modern environmental movement. It captures the essence of what environmentalism is all about: a long view based upon appreciation and understanding of the natural world.

In 1994 a new version of “sustainability” emerged called the “Triple Bottom Line”: three overlapping circles — “Social,” “Environment” and “Economic” — with the word “Sustainable” situated in the middle.

“TBL” equates the natural environment with two things that depend upon well-functioning natural systems for their existence—society and economy. The basic idea behind TBL is that damage to those natural systems can be justified by the resulting short-term benefits reaped by society and the economy.

The tension between protecting and exploiting the natural world is as old as human civilization itself.

Genesis 1:28: “And God blessed them, and God said unto them, be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”

In the 19th century, the concept of Manifest Destiny captured the American imagination and helped fuel expansion from coast to coast, along with an unmitigated rush to exploit natural resources. Native Americans, at best, were looked upon as caretakers until the white Christian owners of the continent arrived to assume their rightful place.

Writer Ayan Rand later summed up this worldview in stark blunt terms regarding Native Americans: “What was it that they were fighting for, when they opposed white men on this continent? For their wish to continue a primitive existence, their “right” to keep part of the earth untouched, unused and not even as property, but just keep everybody out so that you will live practically like an animal …”

With a few tweaks, Rand could have been talking about modern environmentalists and the quest for “sustainability.”

We’re told we have to balance the needs of people with the natural environment. That version of “balance” involves a perpetual splitting of the difference between what’s left of the natural environment and expansion of the built environment. It almost always results in less nature, less biodiversity and less sustainability, with what’s left of our natural world perpetually diminished in the name of progress.

Unlike shoes and tires, though, once we’ve worn down nature’s finite “durability” there is no replacement.

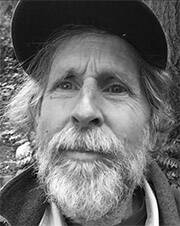

Ron Peltier is a community activist and former City Councilmember.