Steven Djordjevich needed a good idea for his Eagle Scout project. An observation by his mother offered inspiration.

“A lot of people don’t know who William Bainbridge was,” she told him. “Some of them think he discovered this island.”

Djordjevich realized that indeed, nothing on the island described Bainbridge or his accomplishments.

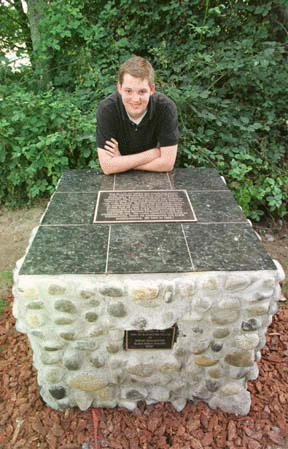

Until now. This Saturday at 11 a.m., Mayor Dwight Sutton will dedicate Djordjevich’s project, a 5,000-pound concrete, river rock and marble structure with a plaque summarizing Commodore Bainbridge’s distinguished career in the U.S. Navy.

Located in Waterfront Park a few steps east of the parking lot by the public boat launch, the monument stands three feet square by just over three feet high.

Djordjevich, a senior at Bainbridge High School began his project not long after his mother’s suggestion.

The first step was to research Bainbridge’s life. Then he drafted a proposal that included a basic design, consultations with architects and contractors, the method of building, where it would be located and numerous other details.

So did William Bainbridge actually discover the island?

No. Born in 1774, he was one of the generation of American sea captains who came of age during the War of 1812.

Rather than attend college, he went to sea at the age of 15 and within four years became captain of a merchant vessel.

He joined the nascent U.S. Navy in 1798 as a lieutenant during the quasi-war with France. Though captured, he was promoted to the rank of captain in 1800 and spent the next few years involved in the ongoing wars with the North African Barbary pirates.

In 1803, he commanded the USS Philadelphia. Lured into a trap by the buccaneers, the ship ran aground and the entire crew was taken into captivity.

Ransomed after more than a year in prison, Bainbridge spent seven years alternating between lucrative merchant cruises and naval assignments.

In the War of 1812, he ascended to command of the USS Constitution, arguably the most famous ship in the Navy’s history.

Under his leadership, the Constitution defeated the British frigate Java, the feat for which Bainbridge remains best-known.

Promoted to the rank of Commodore following the war, he eventually became president of the Board of Naval Commissioners, the rough equivalent to today’s Chief of Naval Operations.

Bainbridge the commodore died in 1833, without coming within 3,000 miles of Bainbridge the island.

So why does the island bear his name?

At one point in his later career, Bainbridge served as commander of a schoolship that trained midshipmen. One young man under Bainbridge’s tutelage was Charles Wilkes (after whom Wilkes School is named).

A generation later, Wilkes commanded the United States Exploring Expedition which sailed past Antarctica and eventually entered Puget Sound. He conferred his former mentor’s name on one of the islands he surveyed.

Monumental

A scout since age 5, Djordjevich took the proposal to the city after it had been approved by his troop leader.

“They approved it within a day,” he said, and also offered to provide the necessary funding, which ran just over $1,000.

Djordjevich purchased his supplies in December, and construction began in late June.

Following a two-month hiatus while he was out of town, Djordjevich wrapped up Sept. 15.

“I’m very satisfied with the way it came out,” he said. “It differs slightly from the original plan, but differs for the better. At first I was going to use cinder blocks, but now it looks more solid and more full.”

There’s no doubt about its solidity. Construction began by hand-mixing and dumping 60 sacks of cement into a D-box. When it dried after a week, the box was removed and the four sides were faced with river rocks.

“That was the hardest part,” said Djordjevich, who gives credit to stonemason Henry Carrillo.

Carrillo also donated the marble that lines the top. The final stage was drilling in the plaques, then barking the surrounding area.

He’s quick to point out that a project of this magnitude depended on the contributions of numerous other people.

Part of the project involved keeping careful records, so he knows exactly how many person-hours were involved: 277, of which 112 were his own. He cited fellow scout Nicholas Stewart, contractor Tom Whealdon and the Carmel family for help.

“We’re lucky to have folks step in to improve the park and the area,” Mayor Sutton said of the monument. “I’m pleased to have it.”