It’s a simple and devastating dilemma: The qualities that make a city desirable can eventually suck the life out of it.

Stunning natural scenery brings bodies to the area, leading to the sullying of the landscape. The promise of vibrant urban living leads to an explosion of luxury condos, which eventually renders in-town living unaffordable. New industry lures wealthy professionals, nudging out families and the working class and leading to clogged freeways and soul-numbing commutes.

“Those dynamics aren’t unique to us; they’re happening all over,” Knute Berger said. “But we’re feeling them acutely because we’re a whole lot less screwed up than other places, so we’re very attractive.”

Um…yay?

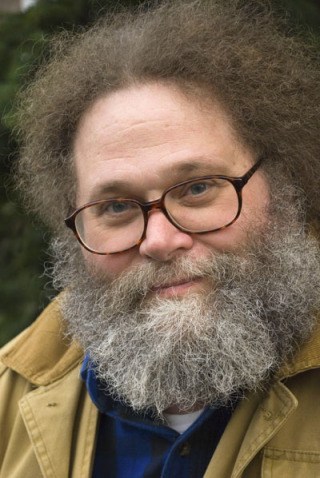

Berger, a third-generation Seattle native, has devoted his journalistic career to examining the ever-present tension among the Puget Sound region of old, the mega-something he believes it’s on a direct course to becoming, and the often unfathomable idiosyncrasies that make up our regional character.

He’s distilled them in “Pugetopolis: A Mossback Takes on Growth Addicts, Weather Wimps, and the Myth of Seattle Nice.”

The collection presents 17 years’ worth of new and past essays culled from Berger’s stints as editor of Seattle Weekly and Eastsideweek; regular commentator on KUOW’s Weekday; and columnist for Seattle Magazine, Washington Law and Politics and the online journal Crosscut. He’s making Bainbridge, familiar territory for him and his family, the first stop on his reading tour this Sunday afternoon.

As cynical and exasperated as Berger can be about Seattle and its surroundings, his work is infused with the spirit of his alter ego.

“The whole idea of ‘Mossback’ isn’t about being a native to the region; it’s about staying in the region long enough to let it grow on you,” he said.

In other words, the essence of Berger’s beef isn’t that people move here from elsewhere. It’s that people move here, disregard the region’s history and character, and try to turn it into the place they came from.

Then, as is part of the modern corporate pathology, they add insult to injury by leaving a homogenized mess behind when their companies transfer them to the next big city.

As such, “Pugetopolis” hammers home a good deal of Seattle-area history along with its rants and musings on current events, all seen through the eyes of a native who came of age during the Civil Rights movement and subseuqently witnessed Californication, grunge-ification, and Bill Gates-ization first-hand. (Call these borrowed and made-up hyphenated words a Berger-esque homage.)

A 2002 Washington Law and Politics piece, “Race in Seattle: It’s Mighty White of Us,” examines head-on a topic commonly avoided like the plague in Seattle. Although the city has grown far more racially and culturally diverse, Berger acknowledges, he busts white Seattleites’ notion that they and their hometown are so enlightened as to be above racial difference. They believe themselves not white but “clear.”

Similarly, in a 1999 Seattle Weekly column titled, “A Fine Rage, a Fresh Wind,” Berger contextualizes the WTO riots that occurred downtown on Nov. 30 of that year. Berger valued the frenzy of that day, not because of the corporal and property damage revealed when the smoke cleared, but because of what the event represented.

For one thing, it counteracted, if however briefly, the disappearance of an active resistance to getting big. “Lesser Seattle” was a tongue-in-cheek movement of yore, but there was a seriousness to it, too, an idea that growth in whatever form should be planned and executed with a clear eye toward a city’s history and intrinsic character – what it was, and is – as much as toward what it could become.

And then there is the phenomenon of “Seattle Nice,” which the WTO Battle in Seattle turned on its ear.

“This was a city that trashed our unofficial motto, ‘If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all,’” he wrote of the day’s events.

For a newcomer to Puget Sound, Seattle Nice – which encompasses everything from the mayor never actually saying “no” to cheerfully waving to your neighbors for 15 years without ever learning their names – is arguably the region’s most confounding phenomenon.

Not that anyone would actually confront you with it, which also makes it the toughest nut to crack. Why did no one knock on my door with a pie when I moved here? Because to a Seattleite, Berger said, drop-in visits are evil.

“I’ve lived next door to people for decades and never talked to them. And they don’t want to talk to me either,” he said. He added that most of his friends are peers in the journalism community, and most aren’t from here originally.

Many of the topics Berger tackles can be ferried across the water, to be applied uncomfortably and thoughtfully to Bainbridge (which falls, according to the outline Berger draws, firmly within Pugetopolis’ geographical limits).

Quiet retreat or vocal community? Density downtown or suburban development? Why is it so hard to make a living wage on-island? Does our zoning restriction on big-box stores matter if all we’re left with in Winslow are real estate offices put in place for the express purpose of selling condos?

And more: What’s the cost of the slow demise of island farming and industry? How can we be a culturally and economically diverse community if a select few – more empty nesters, fewer young adults and families – can afford to live here?

Berger has strong Bainbridge ties, with his parents moving here in 1973. His mother, poet Margi Berger, and sister, children’s book author Barbara Helen Berger, still live here. And he worries about the island.

“Will it sort of turn into Mercer Island, where there’s no agriculture, there’s no working class? Islands are these delicate ecosystems where you’re sort of limited in what you can do,” he said.

Which doesn’t mean do nothing. Berger himself has made a recent foray into historic preservation in Seattle, both writing about and participating in efforts to designate and save landmark properties around the city.

The process, while dysfunctional and fascinating – catch the final essay on the fate of the Ballard Denny’s – hasn’t left him hopeless. Like the Seattle pioneers who carved out their niches 150 years ago, he can envision all sorts of possibilities.

“I’m both cynical about Utopia, and also hopeful that somebody will figure it out,” he said. “At the same time, I wouldn’t want to live in anyone else’s Utopia. That would make me crazy.”