There’s more than one way to follow the stepping stones of progress, and kids of all abilities can make their own path, experts say.

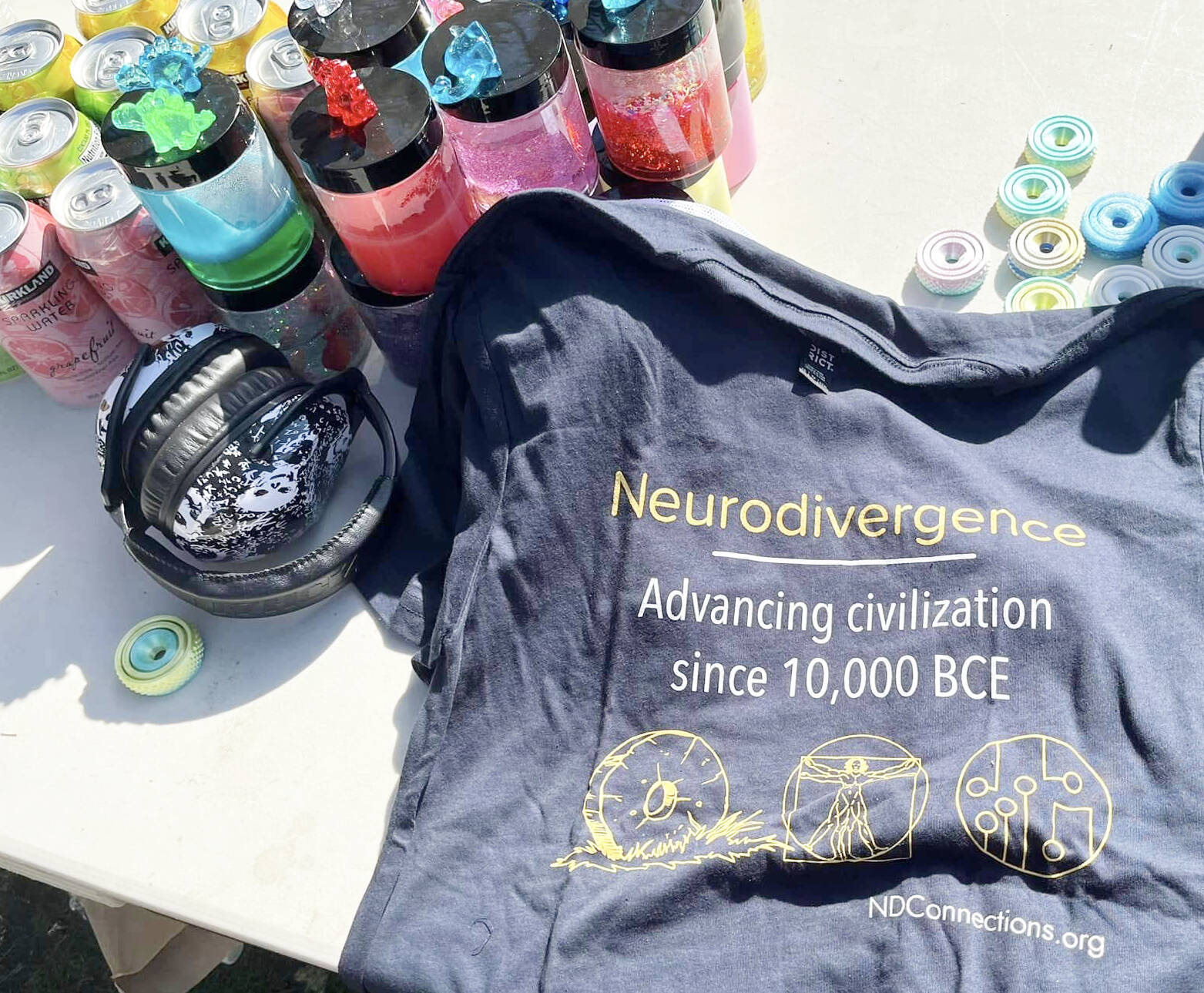

A small collection of private and public education providers in Kitsap County came together March 1 for Bainbridge Island’s first Neurodiversity Symposium, a networking and supportive learning event for families with neurodivergent children.

Sector professionals and representatives from institutions like the BI School District and nontraditional schools like Little Fern Forest in Indianola came together to discuss learning accommodations, what to expect from and how to set goals for neurodivergent students, empathy and celebration of differences.

“The traditional school system is set up like, ‘Our children need to be at this benchmark, then this one later,’ and so on, and as a neurodivergent person, you can learn to adapt and cope for your whole life. But that’s not a reality for a lot of neurodivergent people,” said Meg Wolf, director of nonprofit Neurodivergent Connections.

“You can keep practicing those skills at home, that’s true to some extent. But after a seven-hour day of school, it can be very stressful to continue, and pushing through it can become hard down the road. This was about celebrating neurodivergence, because these kids know what their bodies need.”

Kelsie Olds, an occupational therapist specializing in play, presented their teaching philosophy for how to build life skills for students who struggle with autism or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

The central tenet of Olds’ work is that it’s easier for students, parents and teachers to go with the grain of neurodiversity rather than attempt to cram a square peg into a round hole. In early childhood, that means neurodivergent students are often best-served by accommodation, not behavioral adjustment, but that does not mean the skills kids need to succeed are out of reach, they said. All children, but especially neurodivergent children, learn crucial skills through play, and many can meet development milestones that prepare them for success at school if their needs are met.

“In early years, before school, there are skills that human beings need before they go into an academic setting with academic expectations. These skills need to be in place before children are ready to keep up with physical and behavioral expectations in the school day, like reading and writing,” they said.

Physically, students need enough core strength to sit up, stable joints to hold utensils, visual tracking to play games, and bilateral coordination to use both hands at once. Behaviorally, they need the ability to play with others, comfort with trial and error, problem solving and self-advocacy, Olds said.

That’s why families with neurodivergent students often choose to enroll in outdoor education, Wolf added.

“Neurodivergent people can have nervous systems that are a bit more raw. When you’re learning inside, any classroom has to be able to manage 20 to 25 students. If a student can’t meet the expectations of behavior, it can cause problems for everyone,” Wolf said. “Outdoor classrooms can be easier because the forest absorbs more sound, there’s fewer rules about how to orient your body and you can work on those fine motor skills.”

Neurodivergent Connections organized the event, Hyla School hosted it, and Little Fern Forest provided free neurodiversity-friendly childcare. True to form, with supervision from teachers at LFF, neurodivergent students were able to safely play outdoors and explore textures, colors, motions and more, on their own terms.

“It’s OK to go to school and still need support,” Wolf said. “That’s not a shameful thing — it’s just a different approach. And we’ve always had neurodiversity in human populations. We need every perspective because together, that’s how society functions.”