The term “junk sculpture” might suggest worthless work, but the art Bainbridge High School senior Benj Cameron makes from island trash is both beautiful and expressive.

“I believe we look at the world through a very narrow lens, one that sees items as having one use and one use only,” Cameron says. “My method of sculpting comes from my conviction that ‘garbage’ is often more useful and more valuable than products one can buy.”

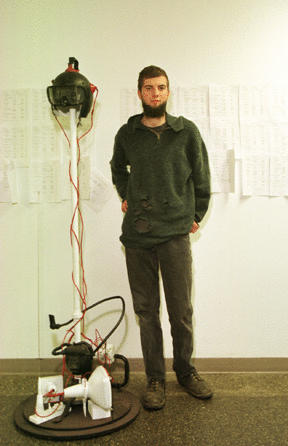

The prolific young artist, whose works are on view at Bainbridge Arts and Crafts in June with other award-winning high school art, has produced a body of work that could translate into a one-person show: 25 pieces since November, ranging in size from eight feet to three inches,

“I work on a lot of pieces at once,” Cameron says. “I’ll start something huge and work until I don’t want to weld or sand it any more. Then I’ll go on to another one for a while.”

Making good junk sculpture is more than welding a roller skate to rebar.

It takes skill and intuition to place one thing next to another to create a new whole.

Successful work of this kind, works like Cameron’s, often look like they were grown rather than fabricated.

In Cameron’s work, a cathode tube turned face down sprouts a crop of twisting wire; pipes extrude a red light bulb, a watch face.

Streams of red, black and white paint unify the surfaces.

Cameron’s inclination, he says, is to work in dualities such as the two plastic guns that take aim at the end of pipes.

“I’m looking for balance,” Cameron says. “Two skulls, two bottles, two guns.”

The pairs of objects often invoke limbs.

That, and the artist’s tendency to affix helmets or abstracted heads to the tops of vertical poles, reinforce reference to the human body.

Adding pounded nails, buzz saw blades and broken glass invokes pain.

Cameron – like others working with “assemblage” – is an aesthetic descendant of Marcel Duchamp, an early 20th century artist whose “Readymades” of found objects included a bicycle wheel and, most notoriously, a urinal.

Among Cameron’s other antecedents are Futurists like Guillaume Appollinaire and Umberto Boccioni, who published the “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture” in 1912:

“A Futurist composition in sculpture will use metal or wood planes for an object …furry spherical forms for hair, semicircles for glass for a case, wire and screen for an atmospheric plane…even 20 different materials can compete in a single work to effect plastic emotion. Let us enumerate some: glass, wood, cardboard, iron, cement, horsehair, leather cloth, mirrors, electric lights, etc, etc.”

Constructivist Kurt Schwitters’ “Merzbau” were cockeyed interiors without a single right angle.

Mid-20th century assemblage artist Joseph Cornell’s magical boxes of select objects have spawned whole schools of lesser windows into smaller universes.

In the 1950s, Alan Kaprow and Claes Oldenberg held “Happenings” in a full-scale assemblage sculpture, “The Storefront” featuring food of paper mache hanging from the ceiling. In the 1960s and 70s, Edward Keinholz extended assemblages into tableau often featuring gritty subjects like abortion.

Lucas Samaras, like Cameron, used sharp-edged materials in his assemblages. In one memorable series of mirrored rooms, Samaras did an installation that was a mirror-lined closet studded with mirrored spikes.

Potential liability might make contemporary curators think twice; then, however, close viewing was an exercise in “caveat spectator.”

Assemblage has a long history – and it is still evolving.

But Cameron has lots of time to meet his aesthetic forebears.

Right now, he can simply enjoy the satisfaction of accomplishment.

“I’ve never played sports,” Cameron says. “I’ve never done anything organized. It’s been good to find this thing I do like.”