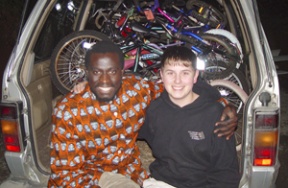

An island student collects bikes for his peers in West Africa.

Most kids would wimp out of biking 10 miles to school, but kids in Togo would love to bike that far instead of walking it.

Bainbridge High School junior Adrian Mason hopes to get bicycles to his peers half a world away for their school commute.

“Kids (in Togo) have to walk an average of 10 miles to school,†Mason said. “I bike to school. It’s something I’m interested in, so I would like to carry it on to other places as well.â€

By June, Adrian hopes to collect 250 working bikes – enough to fill a shipping container – for the Bicycles for Education project of the Global Alliance for Community Empowerment.

He and his mother Maria plan to follow the shipment to the West African country – slightly smaller than West Virginia – located between Ghana and Benin, and to the south of Burkina Faso.

Adrian got involved at Seattle’s Bumbershoot last fall, when he and his mother stopped by a booth promoting fair-trade “shea butter,†and met Olowo-n’djo Tchala (pronounced Oh-lo-WAN-jo CHA-la).

The butter is extracted from the nut of the shea (pronounced “SHAY-uhâ€) tree in Africa’s savannahs, and is an integral part of the Togo culture, used as cooking oil, moisturizer and healing balm because of its vitamins and healthful properties.

As in coffee-growing communities, Togo workers who collect the wild shea nuts used to make shea butter are paid just a fraction of the market price of $1 for two pounds of butter that may take 20-30 hours to produce.

Even the entire $1 price would not be a living wage.

Retail, pure shea butter is $8-$20 for a 4-ounce jar. The market descends from the colonial relationship many West African countries had with Europe.

Tchala, a native of Kaboli, Togo, in 2003 established a fair-trade shea butter cooperative called Agbanga Karite in Sokodé, Togo.

Although there is not yet a formal certification for the product, Agbanga Karite is a member of the Fair Trade Federation.

The co-op began with production by Tchala’s parents and local townspeople who had been part of the conventional trade for decades.

Of the profits, 30 percent are returned to the shea butter-producing communities to help with schools, university scholarships, AIDS and malaria. Global Alliance for Community Empowerment runs the community enhancement projects and is in the process of becoming a 501c(3) nonprofit.

Most importantly, the approximately 70 members of the cooperative are paid 30 percent above the national average – an annual income of $300 – and receive monthly checks regardless of market conditions or the seasonality of the production. They also get benefits such as sick days, pension, vacation and overtime.

“It’s not the efficiency of the organization that matters, but the moral duty,†Tchala said. “I feel responsible to do something about the poverty problem and gender equality overall.â€

As a child, he worked alongside his mother and her friends, laboriously collecting nuts and making shea butter.

“While I was aware of the hard work, and the fact that my mother was never able to make enough money, it was not until I had a more global experience that I was able to see the root causes of this,†Tchala said, explaining that African laborers received meager recompense for their work and resources that the Western world enjoyed.

The co-op emphasizes helping women, who traditionally make shea butter.

From 30 to 50 percent of women are illiterate, making it difficult for them to get work in a traditional sector. Production is the old-fashioned way without use of petrochemicals that reduce the butter’s healthful properties.

Impressed by Agbanga and its mission, Adrian Mason started thinking seriously in January about what he could do to help the Togo nation and its students.

He is currently the only volunteer for the bicycle project, and has handed out flyers at supermarkets to promote the project. He averages four to five hours a week scheduling the pickup of bikes from all over Kitsap, and following up with thank-you notes.

His mother accompanies him on pickups, but everything else is up to him.

To date, Adrian has collected about 40 bicycles, kept in space donated by Reliable Storage.

Tchala takes them to Agbanga Karite’s distribution center in Olympia, where he is director.

“I think that Adrian and (Maria), they are making this one project very possible,†Tchala said. “They truly are living up to their words. They are very committed to help people on the other side of the ocean.â€

Togolese community projects funded by sales of shea butter are managed by GACE and include the Bicycles for Education.

Tchala runs Agbanga Karite’s U.S. office in Olympia, which distributes the co-op’s Alaffia line of shea butter products, cutting out traditional middlemen.

GACE also has projects for conservation of shea trees, school supplies and scholarships and plans to look into biogas – using animal manure as energy – to prevent deforestation for charcoal.

“We do things small scale, trying to turn ideology into reality,†Tchala said.

Wanted: wheels

To donate a bike (in working condition) or bike-related equipment to the Bicycles for Education project, call Adrian Mason at 842-1991 for pickup, or see www.empowermentalliance.org/projects/bicycle.htm for information.

Global Alliance for Community Empowerment: www.empowermentalliance.org.

Fair-trade shea butter cooperative, Agbanga Karite: www.agbangakarite.com or (800) 793-9647.

What is shea butter?

Shea butter (pronounced “SHAY-uhâ€) is an oil extracted from the nut of the shea tree that grows wild in Africa’s savannahs, and is an integral part of life there. Shea trees, unique to that continent, do not produce fruit until they are 25 years old and are therefore not cultivated.

Shea is rich in vitamins A, E and contains various fatty acids. Industries use it as a cocoa butter substitute or in cosmetics.

Agbanga Karite produces what is called “unrefined shea butter†that is made the traditional way, resulting in a smooth and creamy texture, ivory or off-white in color with a nutty aroma. On average, it takes 20-30 hours to produce just two pounds of the butter.

By contrast, the “refined shea butter†process uses petrochemicals and bleaches to make a white, odorless butter with fewer healthful properties.

Shea plays an important role in Togolese culture. Olowo-n’djo Tchala says that before marriage, a woman traditionally had to show that she knew how to make good quality shea butter, as judged by a town elder.

When a man of the Togolese ethnic group Soulani wishes to get married, he will stoically endure a ceremonial whipping – by his future in-laws – to show his love for the woman he is to marry. Afterwards, shea butter is applied to the wounds to speed healing.

In the home, it is used as cooking oil, as there is often no money to buy oil from other sources. The moisturizing and healing properties of the butter are used to help heal the belly buttons of newborns and diaper rash; its anti-inflammatory properties are said to be good for insect stings, burns and sprains.

The red liquid byproduct of butter-making is thought to repel insects and can be used to paint floors and walls of homes.