Editor’s not: The Bainbridge Island Metropolitan Park & Recreation District is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. Each month, we will share a different story about the parks district with our readers.

Battle Point Park has a long and storied history.

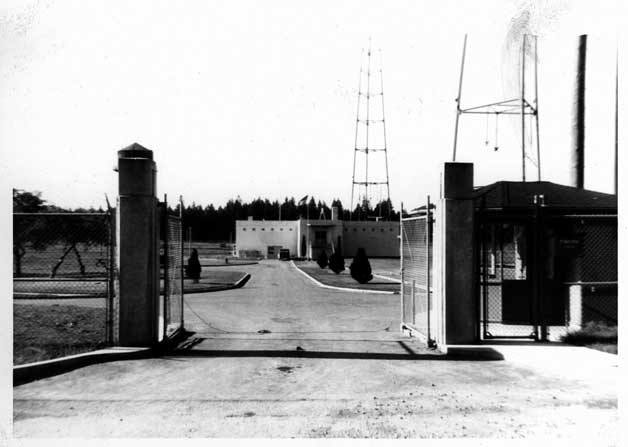

But most of the approximately 400,000 residents who visit the park annually likely have no idea of the park’s significant role over the years. Like the fact that the entrance of the park has the same two pillars and fencing built during World War II to protect top secret clearance work being done by the Navy. Or that the building that now houses gymnastics classes once was a support building for the secretive military work.

According to Bainbridge Island Metropolitan Park & Recreation District files on Battle Point Park, records claim its name came from the Indian battles that took place near the site.

That claim is also backed by Hank Helm, executive director for the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum, who said the name came from a battle between the Suquamish Tribe and Canadian Indians who clashed on Bainbridge Island in the 1900s.

“That’s what the story is,” said Helm. “Indians from Canada were coming down probably to steal women. A signal was sent [off Bainbridge] to let the Suquamish know they were coming.”

A battle ensued, and the very point of the park is where the battle took place, according to historians.

As much of the history of Kitsap County goes, the military took over the island during some of the most important historic chapters of our nation’s history. The Army built Fort Ward on Rich Passage to provide defenses for the already established Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, according to historical records.

“There was a big military presence during World War II,” Helm said.

Code breakers specifically worked from Fort Ward in a secret area where messages from the fleet and Japanese were intercepted. Message content was then sent to Washington, D.C. for administrators to exam, he added.

When the threat of a second World War came in the late 1930s, the Navy took over the fort and expanded it.

During that time, antenna fields to support the top-secret international radio listening station were built on what is now the 90-plus acres of Battle Point Park. Historical documents indicate that as many as 40 men were based at the station at one time.

Throughout the war, radio communication and code schools were built and were used through the Korean War. Here on the island is where code operators learned of the Japanese government’s intention to bomb Pearl Harbor.

Allegedly, the code came through and was sent from Bainbridge to D.C. and sat on someone’s desk on the day of the bombing, Helm said. Official parks department now shows the government stamp of de-classified information regarding the tower and activities surrounding it.

In 1971, the base was declared surplus property and was purchased by the parks district. The 90-plus acres site became the property of the park district on May 5, 1972.

Part of the agreement required that the four radio towers on site be removed so the site could be used by the public.

Days before the towers were torn down, then-director Dennis McCurdy, assistant director Larry Burris and parks commissioner Fred Grimm climbed the tower one final time. It took the pair 90 minutes.

“They ate their lunch at the top,” Helm said with a laugh.

The climb down took a mere half hour.

What once was Bainbridge Island’s tallest landmark — an 800-foot-high steel transmitter tower — was considered by locals as a “terrible temptation to climb” and required the removal of the 311 tons of steel in 1972 before park construction could start. A contractor took down the towers with the promise that he could salvage the materials once finished.

Once removed, the 864th Fort Lewis Engineering Battalion brought its heavy equipment and expertise in to level the grounds as a training exercise while constructing paths and irrigation systems, roads, tennis court foundations, restrooms, parking lots and more.

By 1976, the project neared 30 percent completion and the Army volunteers saved the park district an estimated $100,000.

Even though the tower no longer exists today, the building where coders worked remains and is home to the Battle Point Astronomical Association and its telescope, a much beloved fixture in the park.

During 1973, a general election was held in November that required funds to implement a master park plan. That measure failed, but a special election scheduled for the following year passed with 76 percent approval.

John Rudolph of Bainbridge and Jones and Jones from Seattle were hired to develop the park’s master plan. The levy authorized just over $40,000 for development purposes. The state provided matching funds as well, according to Helm’s research.

Since the time the federal property turned public, there’s been plenty of community support and use, said Perry Barrett, senior planner for the park district.

Grants, monetary donations and volunteer hours have all contributed to the park in some way, including a playground that opened in May 2001.

“It’s the largest active-use park,” Barrett said. “The trails are really popular and the trail connection has been happily pieced together over time to piece the island together.”

As far as design goes, Barrett said the park looks much like it did back in the day. The northern portions are “looser” and more open compared to the rest of the park with its open space, trails and pond. The southern field is flooded with activities scheduled by various sports organizations using the ballfields.

It’s all pretty much the same, minus the military presence and four towers that once dotted the property.

“It has not radically changed too greatly, in terms of general site design,” Barrett said.

As for the future, Barrett said potential plans may include adding a picnic shelter, a garden shed, a possible off-leash dog area and more. The transmitter building, now used for gymnastics classes and camps, was recently renovated but still needs more work, Barrett said. Additionally, infrastructure upgrades, including restroom fix-ups, may also be a part of the park district’s comprehensive plan.

Even with many new parks being added to the island over the years, the support has been strong for more, Helm said.

It’s land like the acreage at Battle Point Park that makes park districts so successful, noted Helm.

“We need parks because parks are very important,” he said. “We all need parks.”