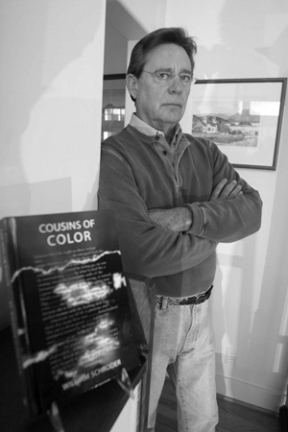

Author William Schroeder looks at the subjugation of the Philippines.

History tells us just three bare facts about Private David Fagen.

We know from U.S. Army records that he volunteered with hundreds of other black men to fight Spaniards in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. We know he was then sent across the Pacific in 1899 to fight Filipinos unwilling to trade Spanish rule for American domination.

History’s parting words on Private Fagen tell us he shed his union blues one night and slipped into the jungle to join the Philippine insurrection.

These facts form only the skeleton of the little-known soldier, but they’re enough to inspire one local novelist to take up his pen and add flesh to the private’s bones.

“Nothing is really known about David Fagen, but what we do know deals with some grand themes,†said Indianola novelist William Schroder, who reads this evening at the Bainbridge library. “I tried to present a picture of a man who sought inclusion and acceptance with his whole world falling apart around him.â€

Crafted over five years, Schroder’s first novel “Cousins of Color†tells the story of a young man searching for the respect few black men of his time ever found.

College-educated and embarking on a promising future, Fagen shifts directions and enlists in the army to prove his valor and dedication to his country. But when he finds himself fighting the very people he came to free, the soldier begins to question his purpose in the war.

Fagen also realizes that Uncle Sam and Jim Crow sailed hand-in-hand to the Philippines, giving rise to a racist doctrine that dehumanizes Filipinos as much as American blacks.

“He knows that every time he pulls the trigger, he helps enslave the people he came to liberate,†Schroder said. “Black soldiers were really conflicted in that fight. Twenty defected, Fagen was only the first.â€

A mix of battlefield action and moral struggle, the book also draws upon exhaustive research that frames Fagen’s fictional exploits within the historical context of one of America’s least-known wars.

The story begins after the United States had overrun Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific with relative ease. After wiping out Spain’s Pacific Fleet in Manila Bay, America found that a long-fought Filipino guerrilla war had grown into an all-out insurrection. Filipinos had elected a president, crafted a constitution and had become Asia’s first republic.

Following Spain’s surrender in 1898, tensions developed between U.S. and Filipino forces near Manila. The American government branded the “insurrectos†outlaws and overwhelmed most of the country by 1902, killing between 200,000 and 600,000 Filipinos. The U.S. held the Philippines as a colony for another 45 years.

While many historians regard the Philippine conflict as a power-grab to expand American markets in Asia, Schroder argues the conflict quickly transformed into a race war.

“America wanted dominance over the Pacific, but because the Filipinos resisted, the pejoratives Americans used against Asians – ‘gook,’ ‘bullet-head’ – quickly turned into ‘nigger,’ ‘sambo,’ ‘darky,’†he said.

America’s treatment of the native population turned brutal, with one U.S. general declaring a policy of extermination for all Filipino males over the age of ten.

Schroder argues that American wartime policies in the Philippines rubbed off on troops and enhanced racial violence at home.

“What happened when these 150,000 troops returned?†he asked. “They’d spent three or four years killing every brown person they saw. What did they then teach their children about the value of a dark-colored person’s life?â€

Schroder said the U.S. suffered a sharp increase in race-based murders after the conflict.

“Violence against blacks spiked, with 1915 to 1925 being the most violent time in our country’s history,†he said.

He also connects the conflict to the present war in Iraq.

“The newspapers were like our Fox and CNN, stirring up support for the war,†he said. “President McKinley was a pro-business conservative who publicly spoke of peace but in private was building up the state militias.

“He made Americans believe the Spanish armada was an immanent threat and that their big guns would destroy us. He said we had a moral obligation to the Cubans and Filipinos and that we needed to rid them of tyranny.â€

Historian Willard Gatewood concurs in his review of the book, stating that readers are “certain to detect analogies between America’s struggle for empire at the end of the 19th century and later struggles waged under various banners in the 20th century and beyond.â€

Schroder said his intent with “Cousins of Color†is not to discredit the U.S., but to present a broader, more accurate view of a conflict many Americans know only by Theodore Roosevelt’s charge up San Juan Hill.

“It’s not America bashing,†he said. “It’s an illusion-free look at history.â€

Schroder said his experiences as a helicopter pilot in Vietnam also gave him a no-nonsense view of wars and the forces that shape them.

“When I was a young man, we were told we were going to keep the South Vietnamese people free by evicting the communists,†he said. “And that sounded like a pretty good deal.

“It wasn’t until later that we saw how immoral our actions were.â€

Having served in combat, Schroder said his portrayals of violence “ring true†and illustrate the grit and trauma of war rather than the “John Wayne†version.

Despite his battlefield experiences, Schroder says he had doubts he could accurately convey the perspective of a turn-of-the-century black man.

“I had my trepidations,†he said. “What’s a middle-aged white guy from today doing writing about a black guy of a hundred years ago?â€

But underneath their skin, both he and Fagen are of one mind when it comes to war, he said.

“I felt a great affinity toward him,†he said. “He was also participating in something he considered unjust.â€

* * * * *

Schroder will discuss his book and the Philippine Insurrection at 7:30 p.m. Feb. 5 at the Bainbridge library. His work is available at Eagle Harbor Book Co.; for more on the book and the war’s history, see www.cousinsofcolor.com.