Two pioneering Bainbridge Island artists helped bring to life a vision of the Yakima River Valley through a glass mosaic designed by elementary schoolers.

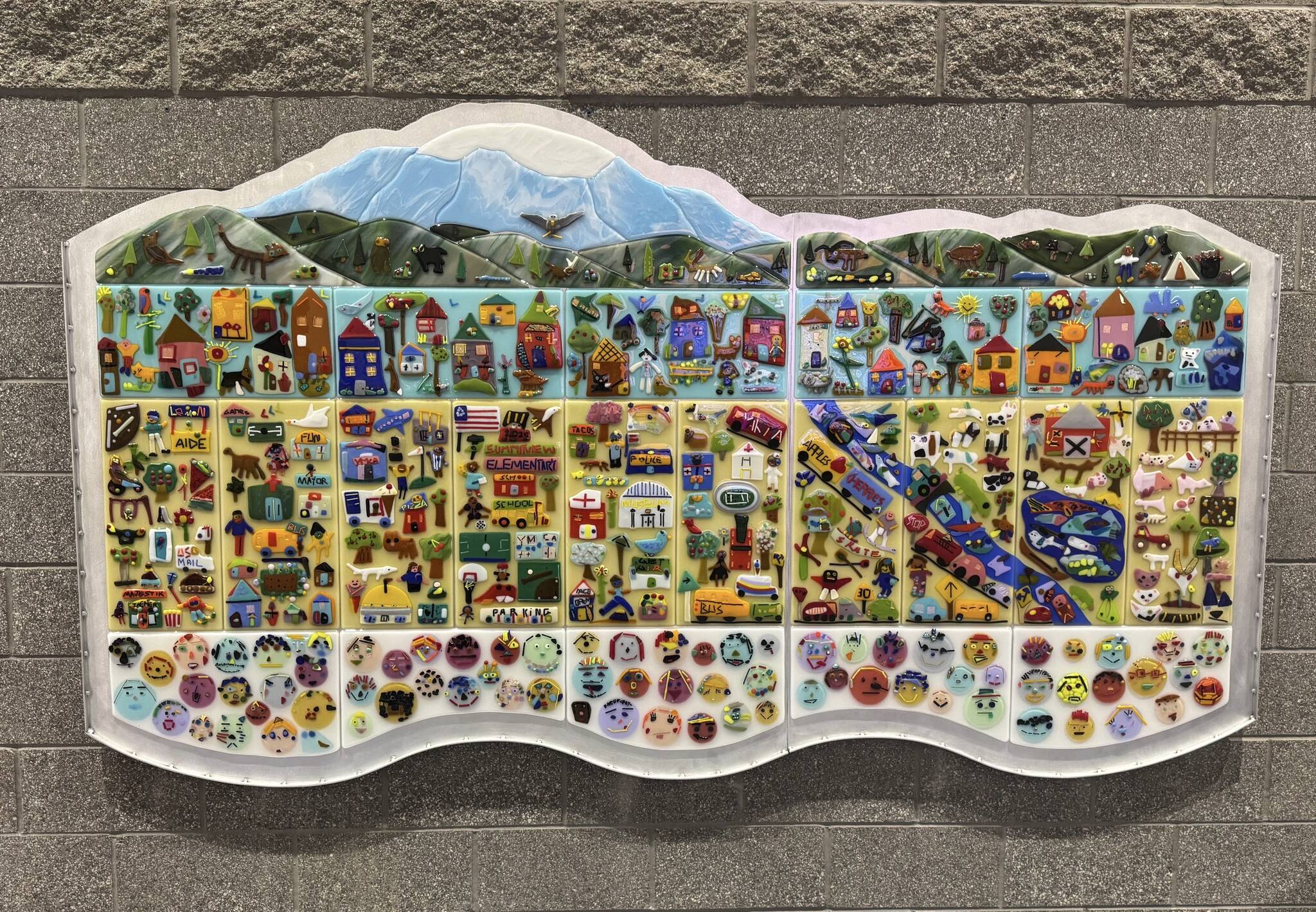

Nov. 13 marked the culmination of a yearlong project led by BI artists Diane Bonciolini and Gregg Mesmer, of Mesolini Glass Studio: a fused-glass mosaic mural installed at Summitview Elementary School in Yakima that captures people, animals, plants and landmarks in the valley from the perspective of about 480 students at the school.

“When it was installed, there was a ton of ‘Oohs and ‘Ahhs, a lot of finding their [piece] with excitement, finding their friends’ pieces. The mural is representing the Yakima Valley where our school is located, from the kids’ eyes, from the students’ vision,” said Danielle Crawford, kindergarten teacher at Summitview. “It was really fun to see them point out the SunDome, or the soccer fields, or the baseball fields, or the Yakima River. They were pointing out all of the things that were in there that are important to them.”

This project joins a dozen or so glass murals that the two artists have created for schools with student help, but this was the first with so many students, and the first in Yakima. Nearly every public school on Bainbridge has a Mesolini piece, except the recently-remodeled Blakely Elementary, Mesmer said, and they’ve worked with two other schools in Western Washington as members of the State Arts Commission roster.

“We’ve really enjoyed taking the ‘work,’ if you will, or the supplies or the material to the schools on the road and letting the kids experiment with it and play with it,” said Mesmer. “The beauty about the Yakima project was, they’ve taken arts out of the schools nowadays, and the kids really took to it. They were just eyes wide open, and very much applied themselves wonderfully.”

Bonciolini and Mesmer, who are married, have been practicing glassmaking on Bainbridge since the mid-1970s, before there was much information available about the art form, they said. Innovation and experimentation characterized their early work and led them to their signature style.

At first, they found traction in the community through local art competitions, which led to stained-glass window commissions, and later functional glass dishware — pieces of which all bear their trademark “live edge.”

“It’s beauty; art is beauty, and if you can, people were buying pieces that were affordable, functional and beautiful that they could use every day — put it in their dishwasher, that kind of thing,” said Bonciolini.

“That’s where fusing and slumping [glass] started, and that parallels how the industry was changing, too — fusing was starting to be a big deal and take off,” added Mesmer. “But the key was, you had to experiment on your own to figure out what worked. With the palette of the glass colors that we had, and manufacturers, having that background was pretty comfortable for us to figure out a direction that we were going to go.”

Without grant funding from the State Arts Commission, Summitview wouldn’t have been able to afford an art installation of this scope, Crawford said.

The state “Art in Public Places” program creates permanent artwork in public buildings and educational institutions, paid and cared for by the State Arts Commission, in perpetuity. Any new capital project construction must set aside 0.5% of construction costs for the public art fund.

When Summitview was remodeled in 2022, it became eligible for a new piece of art, which is how the school connected with Bonciolini and Mesmer.

It was the glass artists’ idea to involve students in the mural, they said. At first, the piece was set to be installed about eight feet off the ground, and created by Mesolini Studio from whole cloth. The two artists convinced the school administration to allow students to design the tiles and to lower the mural to student eye-level after showing them their successful pieces from Bainbridge and other schools, they said.

“Pre- us going there, we had the teachers have the students draw icons that reminded them of certain parts of Yakima — whether they be the hospitals, libraries, trains, farms, animals, playgrounds — and then we have the teachers send those drawings to us. We gleaned them and assigned our different drawings to each student,” said Bonciolini. “There were like 480 kids, and we worked with them three days in June […] The students worked in pairs, so that helped handle that population.”

The students’ icons showed the artists what was most important to them in their community: some had a taco stand, some had playground swing sets, some had people, and some had orchard trees of cherries and other fruit. In June, the couple drove over dozens of types of glass — many colors and textures — and helped instruct the students to create their tiles.

“The beauty…is, they teamed the grades together, so they had fifth grade teamed up with the kindergartners, and then they had partners within that. We really tip our hat to the older kids, because they knew what was going on as a collage type of thing. But you got to give the kids a lot of credit; there’s just a blank slate, and you introduce it to them, and they catch on quite quickly,” said Mesmer. “Kids are so flexible, and they’re so versatile; they’re quite open to new experiences.”

Firing the tiles in the Mesolini kiln — a small oven in the couple’s backyard — took all summer, they said. When they returned to install the piece, students were thrilled to see how their work turned out.

“The real big picture is kids take ownership of the pieces. And as the years go by, they go by and visit the school, and they look at the projects that we’ve worked on with them, and it’s really cool to get the response from them after years have gone by,” said Mesmer.