BI planners vote to move forward Winslow affordable housing project

Published 1:30 am Tuesday, September 16, 2025

Call it what you want — an eyesore or an asset — the proposed housing development at 625 Winslow Way is the talk of the town, and it doesn’t even exist yet.

From 6 p.m. until 1:30 a.m., about 100 Bainbridge Islanders voiced their support, concerns, questions and comments about the project Sept. 11, making the event the largest and longest public meeting ever hosted by the Planning Commission.

By the end of the meeting, commissioners voted 4-2 to recommend that city council make changes to local zoning at the site that would render the project compliant with city code. Those updates would remove one of the last roadblocks to the project’s progress.

While the changes would exceed initial preferences indicated by city council — raising the height limit for buildings to a maximum of 55 feet, or 5 stories, to accommodate up to 90 units — they would only apply to developments in the Ferry and Central Core districts designated as 100% affordable (i.e., 625 Winslow Way).

Commissioners added that any new projects using those new zoning regulations must be affordable for households earning up to about $87,000 per year, or 80% of the Kitsap County Area Median Income, per the 2024 findings of the U.S. Census Bureau.

“We’re faced with a profound question tonight: how do we use one of our premier parcels of public property? It’s asking us to put our community values into practice. The need for affordable housing is an existential crisis for our community. Our schools are shrinking and at risk of closing, and we all know why — families can’t afford to live here,” said commissioner Sean Sullivan. “This project isn’t going to solve all of those problems, but it’s a down payment to start addressing some of these challenges […] We can’t afford to wait another year. The affordability crisis is now, and we have a thoughtful and responsible project ahead of us.”

Commissioners Sarah Blossom and Criss Garcia voted against the zoning recommendation but in favor of the added affordability clause. All six commissioners also voted in favor of a multi-meeting “interface” with the Design Review Board for the project.

About 40% of the construction budget for the project is contingent on funding from two government housing grants: the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit and the state Housing Trust Fund — applications for the latter of which are due Oct. 16.

Federal grants are only awarded at the end of the project, following state support. If a project isn’t code-compliant from the outset, it’s not going far, explained Jon Grant, LIHI chief strategy officer and former Bainbridge resident.

“We will be submitting a letter [to the state] that is what is called a ‘Zoning Compliance Letter,’ that basically says ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ If the answer is ‘no,’ we can try to qualify that answer, but it’s signaling to these public funders that this is not a shovel-ready project, and it could make your project not competitive,” said Grant. “That’s why this conversation is so important tonight. In order for Bainbridge to compete with all the other communities across Washington state, we have to make sure that our zoning codes are in alignment in order to successfully secure those funds so that we can actually bring affordable housing to Bainbridge.”

625 Winslow project leaders — including commissioners, city planners and management from the Low Income Housing Institute, the city’s development partner — spoke to a packed house about their vision for the city-owned site at the corner of Winslow Way and Highway 305. Community members then shared their thoughts and posed questions to the project leaders through public comment.

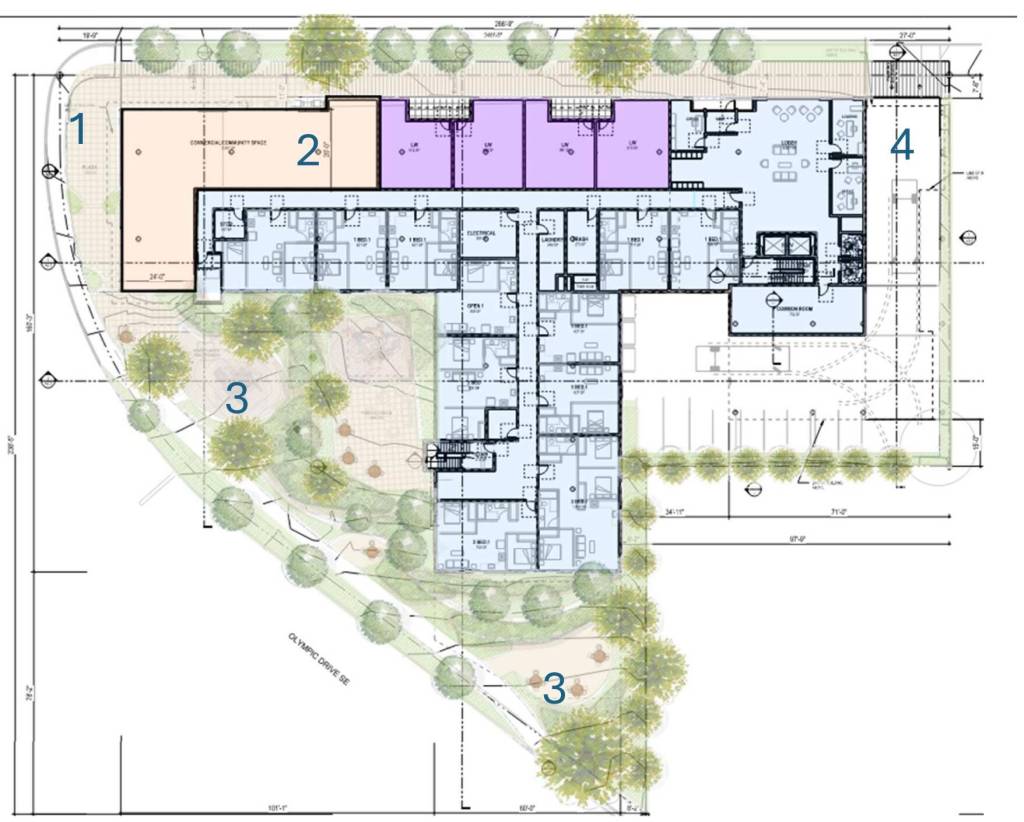

The LIHI team offered rationale for elements of the project that have attracted criticism: its location, its size, its designation as “affordable,” its environmental and traffic impacts and more. Principal architect Michele Wang also reviewed the design philosophy behind initial renderings and noted the amenities the project could provide.

“There is no design yet. It is very early on in the process, but we know this is an important intersection and a major gateway to Bainbridge Island. It’s a location with incredible potential to support small businesses on Winslow Way at the ground floor, enhance the pedestrian experience along Olympic Drive up from the ferry terminal, and add homes in an environmentally responsible way,” said Wang. “We have a wonderful chance to go from an asphalt parking lot to a development where landscaping can repair the site, support healthy habitats, support a vibrant public realm, support connections, all the things that we want for our communities.”

But some Bainbridge residents did not see it that way.

Many meeting attendees took issue with the location of the project, which they saw as an inefficient and potentially hazardous use of valuable public property. Several called for more public input and transparency in planning, noting what they perceived to be violations of the civic process. A few had concerns about population load on the drinking water aquifer in the area, which requires enough rainwater to percolate through the earth to recharge.

Fear that potential occupants of 625 Winslow could take advantage of the housing opportunity was a common theme in many comments.

“Take a walk with me. Pull the theme of ‘first impression,’” said Connie Ballou, longtime Bainbridge resident. “You come here on a sunny day, you get off the ferry, and there’s an apartment building sitting at the edge of the water. You’re curious, you ask, and you find out it’s a low-income housing project that was pushed through the city council, opposed by many people, housing people who maybe don’t even live on the island but found a beautiful, low-cost oceanfront apartment to live in on their subsidized housing revenue.”

Janet Luhrs, a BI resident, added that the project’s process seemed “backwards.” The plans LIHI and the city council presented were not supposed to exist before the appropriate zoning amendments, she said, “but they didn’t do that.

“Why has this project become something that divides, not unites us? Why is it people who want low-income housing versus people who supposedly don’t? That’s not it. Most of us want low-income housing, that’s not what this is about. The issue is where it’s being put,” Luhrs said.

Other attendees disagreed with these characterizations and expressed support for the project.

For one, the island is sorely lacking affordable housing, which is forcing out would-be middle and working class residents, said former Seattle Weekly editor Fred Moody and union labor organizer Scott Pattison, who represents employees at Town and Country and Safeway.

“When I spoke with our members to raise awareness for this project, their eyes would light up with hope and optimism at the prospect of being able to live close to work. This project could be life-changing for so many workers and their families,” said Pattison. “At the center of this discussion is the definition of community, and too often, working people are left out of that definition when they are the very people that make a community run. They allow us to put food on the table, dine out, get coffee, go to the movies, enable our kids to have a great education and so much more. These are critical contributions to the Bainbridge Island community and these workers deserve the chance to live here.”

For another, the area has already become relatively dense with over 300 housing units, pointed out residents Dennis Gawlick and Chris Frey.

“Some may like them, others may not, but I hardly think these 70 to 90 units represent some kind of fundamental tipping point on the island,” Frey said.

Daniel Lipinksi, stormwater scientist and director of industrial services at Clear Water Services, added that because the site is 75% pavement, there is very little water runoff that is able to recharge the aquifer. Any design should include rain gardens and infiltration facilities, he said.

“To oppose this project on the basis of water resource management, but not have an equal fervor for adopting islandwide non-potable water capture and reuse, lawn irrigation restrictions and drought-resistant landscaping is a little hypocritical,” said Lipinski.

Three commenters at the Sept. 11 meeting brought a new concern forward: the obstruction of the sightline between Schweabe and Sholeetsa, the two indigenous Welcome Poles installed in October 2024 representing Chief Seattle’s parents from the Suquamish and Duwamish Tribes.

Stephanie Reese, Denise Stoughton and Yasmin Guggenheimer all cited concerns from Gina Corpuz, an elder and community organizer from BI’s Indipino community.

“The monument serves as a physical representation of an acknowledgement that Bainbridge Island is the ancestral land of the Suquamish people. These Welcome Poles represent to them, and to us, and I quote, ‘We are still here. This is still our land and water,’” said Reese, recalling a conversation with Corpuz. “Gina said to me, ‘They would never build a 3-4 story building in front of the Welcome Pole in Seattle, because they know better. So why are they trying to do it here?’”

Schweabe on Bainbridge stands at the entrance to the Sound to Olympics Trail, facing south. Sholeetsa in Seattle faces west, gazing into the front of a two-story commercial building at Pier 54, home to Ivar’s Acres of Clams and Ye Olde Curiosity Shoppe.

Most people who spoke against the project said they were in support of affordable housing, just not at the 625 site — but only one had specific alternatives in mind.

Matthew Coates, president of Coates Design Architects and one of the most vocal opponents of the project and organizer of the “Save the Corner” campaign, pointed out two nearby sites that he believed could support a similarly-sized housing project: the Pavilion on Wyatt Way and 251 Winslow Way, a nearly two-acre site close to the Winslow Green.

The Pavilion is a commercial property along Madison Avenue and Wyatt Way occupied by Bainbridge Cinemas, a few restaurants and the Blue Canary Auto Repair and self-serve car wash — next to the infamous “Bainbridge Traffic Dot.” 251 and 241 Winslow Way, both of which are on the same parcel, are classified as “undeveloped land,” but county records indicate a few buildings on the land.

In a conversation with the Review, Coates offered a third alternative: keep the 625 project on the city’s property on Winslow, but scooch it back from the corner. By pushing the building further east, the city could build affordable housing and the corner could be turned into a multipurpose public park. All that would be needed is for the owner of the existing building to donate their land to the city, which they have already expressed interest in to Coates privately, he said.

“That particular site (251) is actually a really good site. It’s in a neighborhood area. It’d be much, much cheaper to park, and you can get about the same number of units on that site,” Coates said at the Sept. 9 council meeting. “The second option is the Pavilion to Wyatt Way. We don’t need to change the zoning there, and we can easily get in 100 units. If you really pack them in, by my calculation, get 140 units. That site is much closer to grocery, schools, transit. There’s already a bus stop there, and it’s a much better, quieter, livable setting.”

The 251 proposal may ring some bells. For three years, developers vied to build an 87-room hotel on the site with a restaurant, bar, spa, courtyard, pond and bandshell. Developer Michael Burns had plans to make it the first hotel in the world to achieve Living Building status, a high degree of energy and water efficiency.

But in 2021, when the city council voted to ban hotels in certain areas of the downtown core, including the 251 site, the project was stalled.

“My support [for the ban] is based on the thousands of people opposed to a large hotel in the downtown core, just the general idea,” said then-councilmember Rasham Nassar in 2021. “Large hotels, downtown core, our community does not want that. That’s what this ordinance reflects.”

Coates acknowledged that the community rejected the hotel proposal, but noted that the complaints were mostly concerned about noise. A housing development without plans to host concerts or weddings could be an easier sell, he said.

This would also not be the first time Coates brought a big vision to the island.

Coates designed the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, adjacent to the 625 lot, and pitched a sweeping redesign of the Ferry district in 2022, when the city initially began considering options for its Winslow property. Coates’ proposal suggested a 500-600 seat concert hall, a range of affordable to luxury housing, office and retail spaces, and green spaces.