BI author debuts new book, a ‘grown-up version’ of her first novel

Published 1:30 am Thursday, August 28, 2025

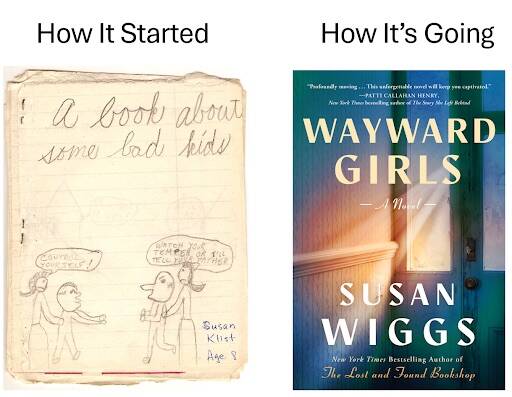

Susan Wiggs started writing about “bad kids” when she was eight years old. She never stopped searching for justice.

Wiggs’ most recent book, “Wayward Girls,” is the “grown-up version” of her first-ever novel, “A Book about Some Bad Kids” — but this time with “better punctuation and a bigger sense of outrage.”

“Wayward Girls” marks her 75th novel, of which at least several have become New York Times bestsellers (she doesn’t keep track, she explained). Wiggs currently lives on Bainbridge Island.

“In one way or another, every book I write is a book about something bad that somehow turns into something good by the end. Growing up as a middle child, I was a keen observer from a young age, and I had the middle child’s sharp sense of justice,” said Wiggs. “Turns out I’ve always had a soft spot for so-called ‘bad’ kids — maybe because they’re usually just misunderstood, overlooked, or stuck in impossible situations.”

The book focuses on the stories of six girls and young women who are sent to a Magdalene laundry near Buffalo, NY — an institution usually run by Catholic nuns that aimed to reform “fallen women” with “behavioral issues” or pregnancies out of wedlock through forced hard labor.

Though common in Ireland and other parts of Europe in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, Wiggs had never known of a Magdalene laundry in the United States. In Ireland alone, an estimated 30,000 girls were institutionalized over the years, and few were ever reunited with their families. In 1993, an unmarked mass grave of 155 individuals was uncovered by a property developer.

That’s part of what drew Wiggs’ attention to the subject, she explained — the mystery was hard to resist. Growing up in western New York in the 60s and 70s, she recalled multiple babysitters who “went away,” but only connected the dots upon a commemorative return to her hometown with her terminally ill brother.

“When we visited the church of our youth, vivid memories of Jon as an altar boy flooded back — especially the time his sleeve caught fire from the incense thurible. This moment sparked a deeper exploration into the impact of the Catholic Church in the 60s and 70s,” said Wiggs. “The more I learned, the more deeply I felt the helpless pain and rage of these young women. Their stories ignited my imagination.”

Many of Wiggs’ novels are historical fiction, but writing “Wayward Girls” was different, the author said.

She accessed court documents, conducted in-depth research at a local library and interviewed dozens of survivors. She tried not to approach “Wayward” like a novelist — for example, forgoing references to her other works in the text — and leaned in to a “grittier lens, a rawer voice, and a flashlight to shine into the dark corners of so-called ‘reform.’”

However, Bainbridge and Kitsap readers may notice a few winks and nods: a BI family claimed naming rights to the dog in the book through a donation to the local animal shelter, and McGavin’s Bakery, Heyday Farm and several other landmarks all are mentioned.

“Probably my favorite moment in the writing of this book was setting down the acknowledgements page,” said Wiggs. “Most readers skip the notes at the end of a book, but in this case, I hope they don’t, because it’s a tribute to readers and how they’ve buoyed my career as a writer for more than three decades.”

While writing “Wayward,” Wiggs saw echoes of the laundries and similar traumatic events everywhere, she said, which lent the process a sad depth. She kept seeing the process repeat: survivors coming forward, apologies coming too late and people still grief-stricken. She was worried at first about the fictional world “Wayward” presented, but some of the survivors she interviewed were grateful to have their experiences revealed at last, Wiggs said.

“The institutions may look different today, but the pattern — of silencing the vulnerable under the guise of ‘reform’ or ‘care’ — hasn’t gone away,” she said. “One of the hardest truths I grappled with was realizing this isn’t just history. It’s legacy. It’s ongoing. And fiction, at its best, can help us look directly at what some would rather keep buried.”