During an appearance in his childhood home of Scranton, Pa. last week, President Biden made the case for congressional approval of his nearly $2 trillion “Build Back Better”agenda, which is in the midst of a tug-of-war between progressive and moderate Democrats on Capitol Hill.

Biden put a particular spotlight on $350 billion for child care subsidies and free pre-kindergarten that the spending plan would underwrite, as he reflected on his experience as a single father who had the help of his family after his wife and daughter died in a car crash in the 1970s.

Millions of Americans, the president noted, don’t have access to that kind of extraordinary support system.

A recently released report underlines the challenges the COVID-19 pandemic economy posed for American women, millions of whom dropped out of the workforce as the economy went into recession.

During the first quarter of 2021, female participation in the labor force dipped to its lowest point since 1988, according to the report, jointly released by the United Way of Pennsylvania, the United Way of Bucks County and the advocacy group ReadyNation. It concludes that the swiftest way to return women to the workforce is for policymakers to “stabilize and strengthen the child care system.”

The report paints a disturbing picture of the pandemic’s impact on working women in Pennsylvania, which reflects the rest of the nation, finding, among other things, that:

• Unemployment insurance claims were higher for women than for men from January 2020 to January 2021, peaking at 22.3% (vs. 19.3% for men).

• More than four times as many Pennsylvania women were unemployed in December 2020 than in December 2019.

• Female workforce participation is not expected to fully rebound to pre-pandemic levels until late 2024.

“Among women, certain subgroups were particularly impacted, including women of color, those with lower levels of education and those in low-wage jobs,” the report says.

Women also comprised two-thirds of the essential workforce and were “key to providing vital infrastructure services and helping to keep the economy running during the pandemic. The pandemic also hit mothers especially hard, with approximately one million mothers leaving the workforce nationwide, compared to half that number of fathers,” the document continues. “Mothers without partners had the sharpest drop in employment among parents. In one survey, 82 percent of mothers leaving the workforce reported that they could not afford to do so.”

Families who were already struggling to seek childcare during the pandemic have seen that search complicated by a staffing crisis within the childcare industry, the report says. In Pennsylvania, 86% of child care providers closed at some point during the pandemic, and at least 850 have closed permanently.

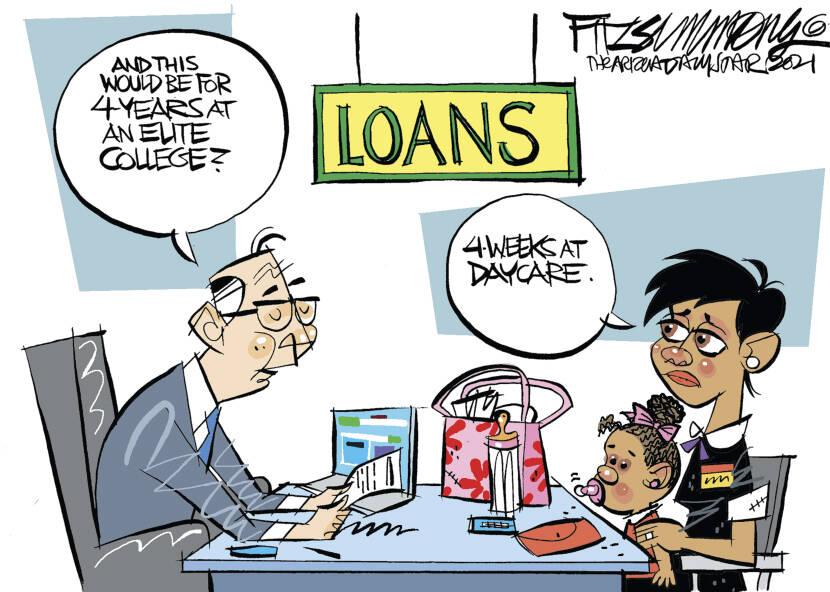

Another 350 providers have remained temporarily shuttered since March 2020. And while 600 new providers have opened during that time they have been run at a reduced capacity, limiting access to care, the report says. The access crisis has further been complicated by an affordability crisis as well, with the average annual cost of “center-based” infant care in Pennsylvania running to about $11,560, which is close to the $14,770 average cost of public college tuition and fees, according to the report.

Again, that reflects nationwide trends. A survey by the National Association for the Education of Young Children concluded that four in five child care centers nationwide are understaffed, and more than three-quarters (78%) said low wages were the main reason they had trouble finding new employees, CBS News reported.

And the economic cost of that crisis is real. Citing a study by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, the report found that the crisis had resulted in an “annual loss of $3.47 billion in tax revenue and to employers’ bottom line due to employee absences and turnover. COVID-19 has likely increased these costs.” And that was just in Pennsylvania.

The report calls on policymakers to expand access to affordable, quality childcare, with state officials leveraging all available federal childcare and pandemic relief funds to prop up the current system and to prevent more shutdowns. In the long-term, the report calls for state and federal officials to “approve additional recurring investments in the childcare sector to address systemic issues like low staff wages, inadequate reimbursement rates for providers participating in the subsidized childcare program and a shortage of high-quality care.”

It’s all well and good to tell American workers that they have to go back to the office. But unless policy-makers back that up with actual action by approving funding for expanded and affordable childcare, such talk is meaningless.

John L. Micek is Editor-in-Chief of The Pennsylvania Capital-Star in Harrisburg, Pa. Email him at jmicek@penncapital-star.com