Bainbridge High School’s biology students are getting a taste of the future by building three food computers.

In essence, the students are building three agricultural crock pots: set it, forget it and reap your crops. The computers are part of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Open Agriculture Initiative (OpenAg). The initiative is working toward the creation of a healthier, more intuitive and sustainable food system.

The personal food computers themselves are climate-controlled boxes capable of accommodating several plants. The computers give the student farmers the ability to control variables which are usually left to nature.

Utilizing hydroponics or aeroponics, farmers can determine how much water the plants get. They can determine how much daylight the plant will receive, and which nutrients to give them. These are only a few of the growth variables that will be placed in the hands of students.

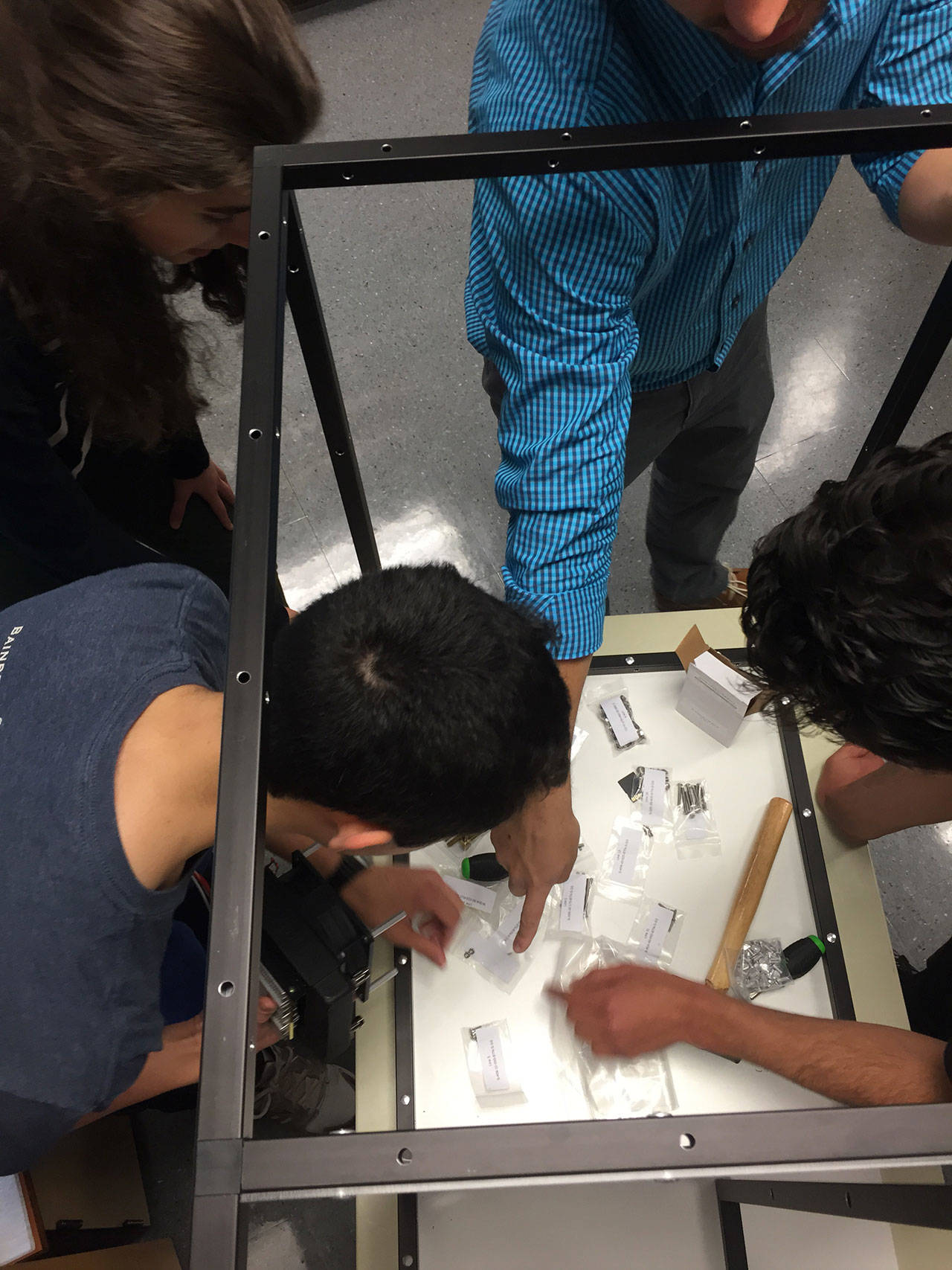

Sarah Lucioni, Andres Rovalo and Steven Albergine are some of the students working to construct the computers, alongside advisors from Fenome.

Lucioni, a senior, became interested in food computers after watching a TED Talk video of Caleb Harper, the founder of OpenAg and co-founder of Fenome, in her biomedical science class.

“I’m interested in computer science and electrical engineering, so there’s an application to it, and I think that’s what’s really cool about the food computers,” Lucioni said.

“There’s so many applications, you can tie them to so many different classes. It’s not just agriculture; you can tie it to computer science, statistics, biology, all of these different classes that could put the curriculum in there and I think that’s really cool,” she added.

Charles Dunn, a biology teacher at BHS, said the introduction of food computers into the curriculum is a big leap in bringing real-world problem-solving to the classroom.

“If we’re going to teach them the scientific method, then that should be part of our core ideology,” Dunn said.

“Students are going to be able to design their experiments, they’re going to be able to give us data, they’re going to be able to then show us what they know,” he explained.

“We’re going to turn them into professional biologists, where they learn information — not because the teacher says so, or the standard says so — because they need to learn it. They need to understand this information so they can do things like help Fenome, maybe not solve world hunger, but address world hunger,” Dunn said.

“Food is a big problem,” Lucioni agreed.

“I think it’s amazing that we produce enough food to feed the whole world and yet we don’t feed the whole world. There are a lot of problems concerning food and food distribution in the world,” she said.

Students will have the opportunity to think critically about how to address issues of global food scarcity using this technology, something the Fenome team is already studying.

Dan Blake, who co-founded Fenome along with Harper, said that the team is already looking into how food computers can be used to feed Syrian refugees overseas.

“We’re working with the World Food Program and the United Nations in building this out to be deployed in Syrian refugee camps in the country of Jordan,” Blake said.

“Currently all of the food that they’re eating in the refugee camps, it’s all being shipped in. We’re looking at the food computers and this technology as a way of allowing them to grow their own food even though they are in the middle of the desert,” he explained.

Blake was on hand in the classroom to help students with building their computers and answer questions from the budding techno-farmers.

He, too, looks at the food computers as a powerful education tool, one which will offer students the ability to engage in numerous scientific disciplines, reproduce “climate recipes” and critically think about how humans can address issues surrounding agriscience.

“It allows anyone to decode any environment and then recode it into any other food computer. When you look at it as an education tool, you have the biology, the chemistry and everything associated with the growing of plants,” Blake said.

“We’re thrilled to work with Bainbridge High and engage the students in building the units,” he added.

On Bainbridge Island, many homes have embraced a sort of pseudo-agrarian lifestyle — one that is not necessarily reliant on the farmer owning acreage or vast tracts of row crops — but instead embraces the backyard chicken coops and carefully planned vegetable gardens which produce just enough to sustain oneself.

As the ubiquity of growing one’s own food creeps up among the ranks of recycling and composting, it would seem that we are watching the beginning of technology intersecting the ancient task of sowing seed. As more people wish to take up small-scale farming, it has become an imperative that the process become more accessible to a younger generation.

Food computers could very well be the greatest agricultural innovation since the advent of the wheel. Using these computers, farmers will be able to grow Iowa corn in Antarctica, or beefsteak tomatoes on Mars, and the students at Bainbridge High will be among the first to learn that neither of these prospects remain the stuff of science fiction.