The Kitsap Public Health District’s first meeting of the Child Death Review Panel was a “rough meeting, heart-breaking.”

That’s what Dr. Gib Morrow, the district’s health officer, said at the April 4 board meeting. “There’s nothing more tragic and upsetting than the death of a child,” he said.

Morrow said even before COVID there was a “mental health crisis” as children were struggling more with anxiety and depression. The social isolation of the pandemic “fueled this fire” even more, he added.

Statistics now show 40% of students suffer from depression, and one in five is suicidal. Nationally, he said suicides are up 70% and homicides 33% among teens, while hospitalizations have doubled, along with overdose deaths. The rates are higher among children of color, he added.

Morrow said firearms were the leading cause of death for children ages 1-19 in 2020. And in the U.S. there is more than one mass shooting a day—“Many in schools, which adds to the anxiety,” he said. He said bullying on social media also has devastating effects on kids.

This type of study of child deaths is needed to find the underlying causes. Only then, through collaboration, can best practices be identified, he said. Processes that could improve the situation include: improved education on health in schools to keep kids safe; coordinated care; family support; suicide prevention hotlines like 988; and more family therapy options.

Also at the meeting, county health administrator Keith Grellner said both the state House and Senate budgets include $100 million more for public health over the next two years. And board chairman Rob Gelder said he was leaving to take a job in Thurston County so the board needs to find a new chair. Poulsbo mayor Becky Erickson is vice chair.

Water and sewer

The program for the board was about Kitsap sewer and water. Grellner said the county is working to better inform the public about sewage spills, which happen most often with large city systems.

Morrow said he is astounded by the location and density of septic systems for household effluent in Kitsap, with some near streams and water sources. He said while they work to make sure such systems work appropriately, there is public health concern because of climate change warming. It creates a challenge to protect drinking water and aquatic habitats, he said.

The presentation was given by John Kiess, environmental health director; Kimberly Jones, sewage manager; and Grant Holdcraft, Pollution Identification and Correction manager.

Kiess said their programs to keep the waterways clean are a model for the nation as the septic and water-quality programs work together. He said there are 11 inspectors who spend up to 70% of their time in the field.

Jones said there are 57,000 septics in the county with the average age 33 years. “If properly maintained they do last quite a few years,” she said. If sewer is not available to a property, her team helps figure out if septics are feasible by evaluating soils; looking at wells, surface water, groundwater, streams and lakes; and making sure drain field soil is dry so it can purify the sewage.

Her department inspected 350 septics in 2022 before they were covered up. Also inspected were 201 repaired drain fields. “We have a strong maintenance and monitoring program,” she said, adding gravity septics are inspected every three years. There are about 12,500 new septics with “whistles and bells” that have licensed maintainer contracts requiring inspections more often than that.

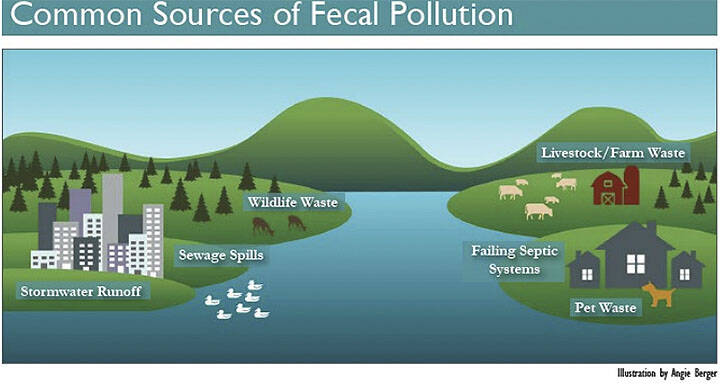

Holdcraft said fecal pollution can be caused by stormwater runoff, wildlife, livestock, septics and sewage spills. His PIC team corrects those problems, usually by following up citizen complaints.

They sample stormwater flowing into Puget Sound, and if there is a high bacteria count they track down the source of the pollution. “Education is one of our most treasured duties,” he said, adding they teach homeowners how to fix problems, which help systems last longer.