In the spring of 1943, a wounded artist crafted a simple black-and-white painting from the hospital bed of the prison camp where he was being detained and almost accidentally created the first great image of the post-Pearl Harbor Japanese internment.

Nobody else could have done it. The man was an artist, an intellectual and a detainee himself; the perfect convergence of skill, interest and experience to immortalize the nation’s then-ongoing shameful misstep.

Then, nearly 75 years later and in a once more tumultuous political climate, the painting ended up becoming just another piece in a pile of stuff — some trash, some treasure — at a curbside Bainbridge Island Rotary auction donation site. It was saved from indefinite obscurity, or worse, by mere chance.

And now, after tireless research and an investment of great time and effort by a select few, who recognized early on the potential importance of this particular donation, the where, when, why and how the picture was made is at last known.

We know who painted it. We know how it became, at least temporarily, famous. But neither of those things are the star of this story. That role, oddly enough, the identity of the mysterious donor, remains unknown — for now.

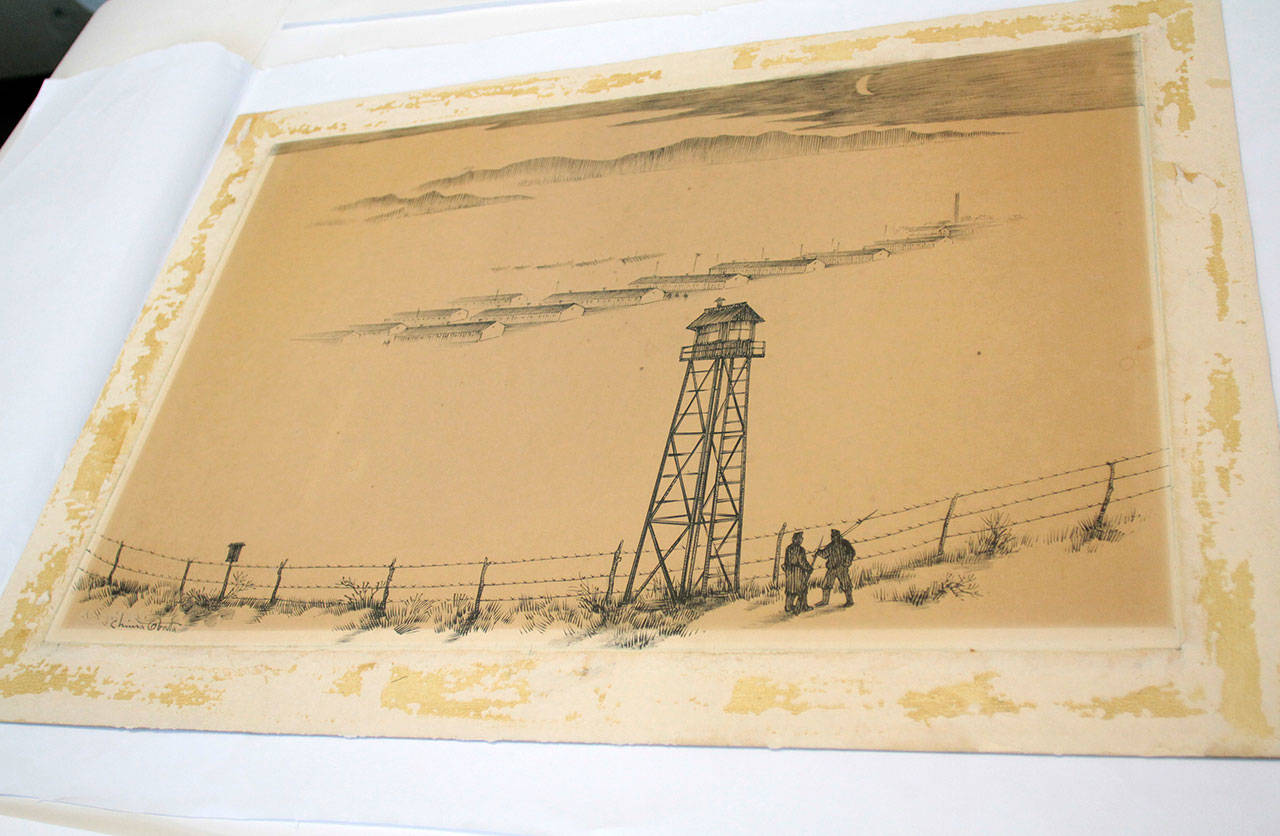

The story of Chiura Obata and his untitled painting of the Topaz Japanese American Internment Camp in Utah is a truly American saga; a tale of immigration, struggle, triumph, tragedy and a whole lot of luck — good and bad. There could perhaps be no better place for its conclusion than Bainbridge Island, being ground zero for the events that began the whole historic affair.

But even when all the pieces come together and nearly all the blanks have seemingly been filled in, there remains one very crucial void: Who donated the painting?

Persons unknown

“It came out of nowhere,” Rotary spokesman Richard Brown said. “A car pulled up, opened the door and a bunch of stuff was laid out on the distribution table and it was taken to the [auction’s] fine arts department. That’s it.

“The people in the fine arts department looked at it and said, ‘This is something that maybe we shouldn’t sell.’ It’s been sitting now since then, and Greg’s been doing research on it to tell us more about it and we’ve been asking questions.”

Greg Brown, an appraiser and broker specializing in fine art and antiques, donated his time and talent to finding answers. In this particular case, he said, it was understood from the start that this client was less concerned about the monetary value of the piece and more interested in its history — and so was he.

“It was a labor of love and respect for the Rotary,” he said. “It’s not like a Picasso. It’s the history that’s so incredible about this, and the path I had to follow was really cool.”

Having filled in most of the gaps in the painting’s history now, the appraiser is hoping to close the case by finding the donor and learning how the piece came to Bainbridge Island. Anonymity can be assured, if desired, and anyone with information about the painting is being asked to contact him at gregcbrownassoci ates@gmail.com.

“We would like to know the provenance,” Richard Brown said. “We know where it started and we know where it went, to a point, and then it disappeared and showed up at the Rotary auction.”

Get the picture?

The painting is a monochrome mixed nihonga (new-style Japanese painting) and sumi-e (traditional Japanese black ink painting) style, according to Greg Brown, depicting the World War II-era Topaz Japanese American Internment Camp near Delta, Utah. It is signed: Chiura Obata.

Obata (1885-1975) was a renowned Japanese artist and art professor at the University of California, Berkeley, from 1932 to 1954. What happened between those years? That’s right, his teaching career was interrupted in a big way by World War II and he spent more than a year in internment camps.

Easy as the artist was to ascertain, the rest of the story was murkier.

A careful inspection of the piece revealed clues as to who matted and framed the picture. Strangely enough, it was marked as “Custom Framed by Dept. of the Interior,” which Brown found odd.

And, even odder, he found mysterious handwritten blue notations on the picture that seemed to come from a different source altogether.

After speaking with Obata’s granddaughter, Kimi Kodani Hill, the appraiser learned that Dr. Dorothy Swaine Thomas, of the University of California, Berkeley, had been doing a large scale sociological study of the internment as it happened and that she’d published at least one book on the subject. Several of Obata’s works that had been used for publication before had had similar blue markings, and so Brown tracked down Thomas’ bibliography and, sure enough, found a very likely contender.

Turns out the painting had been used as the book jacket image for Thomas’ most famous work: “The Spoilage.” Published in 1952, the book is a study she coauthored on the forced evacuation, detention and resettlement of West Coast Japanese Americans during and after World War II — a study funded largely by the Department of the Interior.

“I looked into Dr. Thomas in association with the [framer’s] address, and with the terms Tanforan and Topaz, the two camps where Chiura Obata, the artist, and his family had been held,” Brown said in his appraisal report. “I also called the University of Berkeley’s Sociology Department and from there the Bancroft Library, where Dr. Thomas’ records are kept from her internment research.

“I found out that Dr. Thomas’ work group on the internee experience, which she was the director of, [was] originally started before the internment took place by a couple of her Nisei students after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and then after the evacuation started, she chose the closest detention facilities initially, which included the Tanforan detention facility (a holding area before the internment camps were built and ready), and then expanded to try to follow them through their internment upon their transfers to their ‘permanent’ locations at the internment camps, Topaz being one of them.”

Savvy as she was as a researcher, Thomas was no slouch politically, either. She and her researchers managed to work in and around several camps despite tight government restrictions and she secured hefty private donations, from Milton Eisenhower, the Rockefellers and others, to ensure completion of her studies, to the tune of $100,000 (that’s about $1.5 million today).

“Dr. Thomas even had enough clout and/or authority to have had several people originally sent to, and/or relocated to, certain camps which would aid in the efficiency of her research,” according to Brown’s report. “[She] even helped to get some internees released to Chicago by helping to make arrangements for their work and housing … including Prof. Obata and later his family.”

Though Thomas herself had little involvement with the Topaz camp, Brown was able to find at least one place where the artist prisoner and the intrepid researcher probably crossed paths directly, long enough at least for a painting to change hands.

Bad place, right time

Tensions were running high in the Topaz camp following a dispute among internees about controversial loyalty oaths. Obata was attacked amid the mounting unrest and admitted to the camp hospital. He completed at least one known painting while there, a picture of the hospital interior, which is very similar in style to the mystery painting in question. According to Brown, it’s very likely that Obata had limited painting supplies in Topaz at all, and even less during his time in the hospital, so the brush strokes in both pictures may be more than similar, they may have been done with the same brush.

“[Thomas] had limited work with the Topaz camp, but in her documents, it does appear she may have visited Topaz some time between March 30 [and] April 8, 1943,” Brown’s report said. “If this is correct, it was just after Obata was attacked.”

Brown found at least one direct reference to Obata in Thomas’ correspondence, and, shortly after being released from the camp hospital, Obata was allowed to leave Topaz and go to Chicago. He eventually moved on to join his son, an architecture student in St. Louis, Missouri.

“I suspect … Dr. Thomas visited him there in the hospital, and asked him to do the artwork at the time based on her descriptions of the work she was conducting and the purpose thereof, which was later used as the dust jacket cover work for ‘The Spoilage,’” Brown wrote. “What is strange is she clearly does not mention him in any of the documents I searched within so far … However, he is clearly cited as the artist on the inner front dust cover of the book, so she clearly had some level of contact with him.”

Brown said Thomas undoubtedly was “aware that [Obata] was a professor of art” at U.C. Berkeley, but was surprised “there is no obvious correspondence between them.”

“However,” he wrote, “if she even met him for the first time just before he left the camp in April to go to Chicago, and then to Missouri to be with his son Gyo Obata, maybe that explains this a bit — just a short-term relationship until his return to Berkeley after the war.”

A chilly trail indeed

What we don’t know is what happened next.

Did Obata intend for Thomas to keep the painting? Did she mean to someday get it back to him and their paths just didn’t cross again? What happened to the picture next and where has it been all this time?

How did it get to Bainbridge Island and, perhaps most importantly of all, who donated it to the Rotary?

We just don’t know.

“It got up here somehow,” Rotarian Jim Laws said. “We’re not sure what we want to do with it yet.”

Laws and Richard Brown have been working closely with Greg Brown and following his research into the painting’s mysterious origins. But even as their original questions were answered another came to light: What to do with the picture?

“We’ll probably end up giving it to somebody appropriate,” Laws said. “Either the internment center here or there’s a couple museums that specialize. It’s not an income generator for the club.”

Still, it’d be preferable, Laws said, to know for sure how the picture came to them before making the eventual hand off.

“Whoever we end up giving this to, it’d be nice to give it to them with the whole story,” he said. “The auction is such an amazing thing. One of the really fun parts of this particular thing is how this all came about and the good that it’ll do going forward. Whoever we give it to will really like it.”

Having waded through the dust and details personally, Greg Brown agreed. However the story ends, it’ll be a happy one.

“It benefits humanity no matter what,” he said. “This is one of the coolest things about this story. It came to the Rotary for free. The Rotary is then going to sell it, which will provide money for their charity, or they’re going to give it to another charity, which is going to provide the benefit of the human history and the background behind it.”

If pressed, Brown said he suspects it was a relative or descendant of Thomas or a colleague, friend or student who donated the picture. There will most likely be some kind of connection to Berkeley, if not to the college specifically.

“The joy of this work, because it was done pro bono publico for the Bainbridge Island Rotary, was that I was not limited by a client’s budget, and an inability to follow up every single possible lead in order to put this story and thus provenance together,” Brown said. “This allowed me, out of the love of finding the truth through the facts, be that a positive or negative result in the end for a client, which in this case was a very positive result, and my respect for the Rotary’s higher purpose [to spend] a huge amount of time allowing my nature as a researcher to just let go and have fun pursuing this to the end.”

That is, as much as an end as there can be for now.

So, how about it?