Before HDTV, before VCRs, before television – oh, heck – before electricity, people used to entertain themselves on Christmas Day with an event called the Side Hunt. Essentially, teams would compete to see who could kill the most small defenseless animals and birds as possible.

One year, orinthologist Frank Chapman had another idea: rather than pointlessly blowing their brains out, why not count the birds instead?

To say the idea caught on is an understatement – 110 years later, the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count is the longest running wildlife census event in the world.

Like the birds themselves, the rules evolve, but one constant remains: The only shooting of birds allowed during a CBC is with a camera.

“It’s a fun way to spend the day,” said wildlife biologist Lee Robinson, who with husband Kirk, has counted birds on Bainbridge for 20 years.

Fun, that is, if you like traipsing through the forest, combing the shoreline, and standing statue-like from sun up to sundown, all in the quest of a bird.

“We are exhausted by the end of the day,” she said.

But, it’s all about finding the rare bird, right?

Uh, no.

“Finding the rare bird gives the spotter bragging rights,” said naturalist George Gerdts, who leads the north Bainbridge Island CBC team. “But the out-of-range or out-of-season bird probprobably won’t survive the winter. Statistically, they are not that important.”

“We’re more interested in looking for trends,” Robinson said. Like the disappearance of the Ruffed Grouse or the decline of the Western Grebe.

Consistency counts

To keep the counts consistent from year to year, the CBC divides territories into 15-mile diameter circles, or roughly 177 square miles each. Volunteer teams count all the birds they see within a pre-designated 24-hour period that falls within the CBC timeframe. In 2009, counts must be done between Dec. 14 and Jan. 5. Bainbridge Island’s count, under the auspices of the Kitsap Audubon Society, is Dec. 19.

Bainbridge Island is divided north and south, at High School Road. Also, Seattle’s 15-mile radius was strategically set at Pioneer Square, Gerdts said, to include portions of the rich habitat on Bainbridge’s eastern shores.

Birding’s uglier side

Now you might think birding is a peaceful spectator sport for passive tree-hugger types, but birding has a little known dark side.

“It’s very competitive – and very expensive,” Robinson said.

Not only that, but there seems to be a division among the ranks that has led to a bit of – eegads! – name calling.

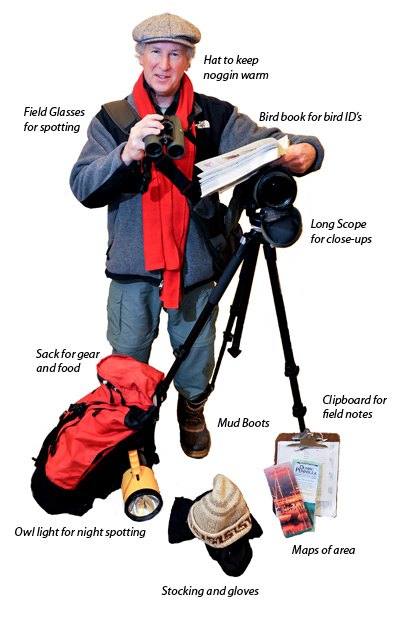

“Bird Nerd” is not a term of endearment apparently. And birders at a recent Kitsap Audubon meeting referred to other members as “hard-core” birders. The distinction has to do with the cost of scopes and how early one is willing to get up in search of a particular species.

By that standard, Jamie Acker is certifiable. As Bainbridge’s resident owl expert, and the CBC owl counter, he has to be out in the field pretty early for a tally of the nocturnal birds.

Bird Nerd, on the other hand, is aimed at those with bird-related email addresses, license plates or, the clincher – the loon ring tone.