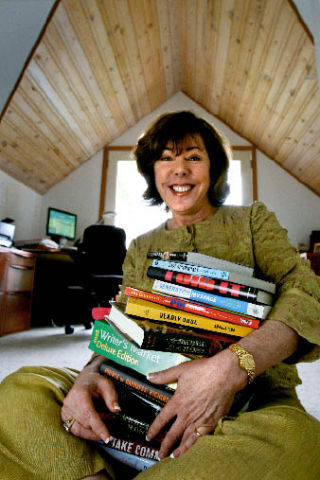

For Sharlene Martin, here’s the fun part about being a literary agent:

“I wake up every morning, and my job is to make dreams come true.”

That said, Martin won’t wave a magic wand to get an author’s book published, no matter how good it is. In fact, she expects a lot of Cinderella-esque legwork – the kind the princess undertook before her transformation – from every writer she represents. Publishing, she believes, is as much about commerce as it is about art. Possibly more.

“What I am is a businesswoman who loves the business of writing and publishing,” she said.

A scant month ago, Martin left the Los Angeles-based offices of Martin Literary Management in the hands of staff and opened a satellite office here on the island. Not only is Bainbridge close to her grown kids, both in Seattle, but it’s also a literary magnet whose pull she couldn’t resist.

Most readers get that Bainbridge contains a disproportionate number of writers and published authors for an island of its size. So it’s a novelty to learn about the process of publishing from Martin’s end.

For starters, Martin receives roughly 1,000 queries per month in e-mail, her much-preferred format. And she answers every one.

Clearly, the number of times she says, “tell me more” is significantly lower than that. But budding writers might be surprised to learn that despite the odds, there are still concrete steps any author can take to get on her radar.

First off, an initial query should be professional and always written. Or in Martin’s case, e-mailed, since she recently decided to take the business fully electronic.

And never phone an agent.

“Sounds good,” she’ll tell someone after a pitch, “but I can’t tell from the sound of your voice what kind of writer you are.”

Much wisdom can be gleaned from tales of how not to craft a query letter when seeking representation by a literary agent. In the December 2007 issue of Writer’s Digest, Martin produced a slew of hilarious examples, all real, ranging from the absurdly brash to the bizarrely clueless:

“I’m finding finding an agent is not so fun a task,” read one inquiry. “Could you e-mail me a couple of addresses and links of agents? I have a stack of books to sell. Like a hermit I write for an aeon then I come out of my lair.”

Or, “My book rocks. You could thank me for even taking the time to let you drool over it. Shucks. I’m even going to propose to let you represent me, ‘cause today is one of those days.”

Seems like a no-brainer, but in Martin’s experience, many writers don’t even spell-check, much less get the basic concept that a query letter is both a writing sample and a sales pitch.

“Just like the line in ‘Jerry Maguire,’ you gotta get me at ‘hello,’” she said.

If Martin replies to a query affirmatively and requests a manuscript, the writer should prepared to produce one post haste. Don’t use an agent to test the waters; no one will wait for someone who lamely says, “Wow, my computer just died. I should be able to have it to you in a month.”

“Ideas are a dime a dozen,” Martin said. “And it’s all about the execution of the idea. If you, as a writer, can’t execute your idea onto the page, then it’s useless.”

Having caught her eye, and then having submitted a worthwhile manuscript, an author next has to be prepared to internalize, nay, embrace the idea that publishing isn’t just about writing great stuff.

It’s about educating yourself about how publishing works, and doing whatever possible to set yourself apart from the roughly 175,000 other books that are published each year – and, once they’re published, have limited time to prove themselves on shelves before they’re returned to the publisher.

That’s publishing reality. Martin recently read a statistic saying that the return rate by bookstores to publishers is 50 percent. In other words, half the books that make it to shelves are eventually returned because of poor sales.

Only 10 percent of writers, she adds, ever earn out their advances; huge advances are a thing of the past. Discovering a million-dollar manuscript in the slush pile at a major publishing house is similarly rare; editors are too busy promoting writers who have already promoted themselves.

“(Some people think that) when you’re a book author, all you need to do is write a book,” Martin said. “But there’s so much competition that you’ve got to find a way to make yourself stand out.

She calls the secret ingredient to distinction a “platform,” or, jokingly, “the dreaded ‘p’ word.” It’s the schematic for how a writer is to present his or her work, persona, package. In business – and again, Martin stresses, this is a business – it’s known as a marketing plan.

Platform components can include Web sites, blogs, public appearances, trade shows and multimedia elements, among other tools.

One relatively new promotional tool that meshes with Martin’s film industry background is the book trailer, a well-produced short film that sets up a book exactly the same way a movie trailer sets up a film.

There’s no limit to the ideas, and part of the fun of Martin’s job is discovering the most effective, and cutting-edge, inroads.

“People who come to me for representation come to me because they like that out-of-the-box approach,” she said.

In the spirit of entrepreneurship, Martin applauds the practice of self-publishing, citing the relative facility and economy with which writers who might not otherwise have risen above the crowd can now get a book out there.

A self-published book with a track record can even become a marketing tool in and of itself. In 2003, Oregon native Suzanne Hansen self-published “You’ll Never Nanny in This Town Again,” the true-life tale of her days in the wacko world of Hollywood childcare.

Through her own determination, Hansen sold 5,000 copies, making enough self-promotional impact for Martin to take notice and shepherd the writer through an auction and eventual six-figure deal with Crown.

The lesson to take away from stories like Hansen’s, and those of other successful authors Martin represents, is that smart legwork can pay off.

So, she recommends, take classes. Attend workshops like Bainbridge Island’s own Field’s End, which offers monthly roundtables with published authors. Take time to learn the etiquette and to think about what might at first seem like distasteful or uncomfortable topics like self-promotion.

Then, if your work is high-caliber and someone like Martin thinks it’s worth selling, she might just help you make your dreams come true.

Next up for Martin is getting to know Bainbridge and its eclectic community of writers. She’s also teamed with Anthony Flacco, her partner in life and business, to write a soup-to-nuts guide for Writer’s Digest whose working title is “The Tao of the 21st Century Non-Fiction Writer.”

Call it an author’s road map to publication, and survival.

“Writers have this responsibility to their readership to be successful,” she said.